- Joined

- Nov 20, 2007

- Messages

- 11,815

- Reaction score

- 640

- Points

- 188

MESSENGER Mission News

October 15, 2008

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu

MESSENGER Gains Speed

Shortly after 4 a.m. this morning, MESSENGER reached its greatest speed relative to the Sun. The spacecraft, nearly 70% closer to the Sun than Earth, was traveling nearly 140,880 miles per hour (62.979 kilometers per second) relative to the Sun. At this speed MESSENGER would traverse the distance from Earth to Earth’s Moon in only 1.7 hours!

Even at this great speed MESSENGER is slightly slower than the fastest spacecraft: Helios 2. That spacecraft – launched into a solar orbit on January 15, 1976 – reached a top speed of 157,078 miles per hour (70.220 kilometers per second) relative to the Sun in April of 1976.

Because of MESSENGER’s near-perfect Mercury flyby trajectory on October 6, the mission design and navigation team decided that a trajectory-correction maneuver (TCM) scheduled for October 28 will not be needed. The next maneuver for the mission, scheduled to be carried out in two parts on December 4 and December 8, will re-target the spacecraft for the third and final encounter with Mercury in just under a year on September 29, 2009.

New Color Images of Mercury Available

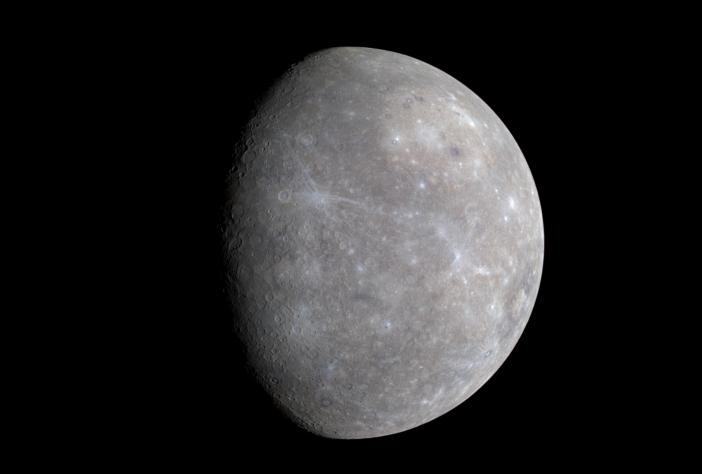

The MESSENGER Science Team has released five new images from the probe’s second flyby of Mercury. To the human eye, Mercury shows little color variation, especially in comparison with a colorful planet like Earth. But when images taken through many color filters – such as the 11 narrow-band color filters on the Mercury Dual Imaging System’s Wide Angle Camera (WAC) – are used in combination, differences in the properties of Mercury’s surface can create a strikingly colorful view of the innermost planet.

Here are four images of Mercury. The image in the top left is the previously released grayscale monochrome image taken with a single (430 nanometer) WAC filter; the remaining three images are three-color composites, produced by placing the same three WAC filter images with peak sensitivities at 480, 560, and 630 nanometers in the blue, green, and red channels, respectively. Shown here are two color images of Thākur, named for the Bengali poet, novelist, and Nobel laureate influential in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In both the optical navigation images and the full-planet WAC approach frame, a bright feature is clearly visible in the northern portion of the crescent-shaped Mercury. This Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) image resolves details of this bright feature, showing that it surrounds a small crater about 30 kilometers (19 miles) in diameter, seen nearly edge on.

This pair of images illustrates the dramatic effect that illumination and viewing geometry (i.e., the angle at which Sunlight strikes the surface, and the angle from which the spacecraft views the surface) has on the appearance of terrain on Mercury. And this NAC image, taken about 85 minutes after MESSENGER’s closest approach during the mission’s second Mercury flyby, shows a view of Astrolabe Rupes, named for the ship of the French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville. Rupes is the Latin word for cliff.

Additional information and features from this encounter will be available online at http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/mer_flyby2.html, so check back frequently to see the latest released images and science results!

MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) is a NASA-sponsored scientific investigation of the planet Mercury and the first space mission designed to orbit the planet closest to the Sun. The MESSENGER spacecraft launched on August 3, 2004, and after flybys of Earth, Venus, and Mercury will start a yearlong study of its target planet in March 2011. Dr. Sean C. Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, leads the mission as Principal Investigator. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory built and operates the MESSENGER spacecraft and manages this Discovery-class mission for NASA.

October 15, 2008

http://messenger.jhuapl.edu

MESSENGER Gains Speed

Shortly after 4 a.m. this morning, MESSENGER reached its greatest speed relative to the Sun. The spacecraft, nearly 70% closer to the Sun than Earth, was traveling nearly 140,880 miles per hour (62.979 kilometers per second) relative to the Sun. At this speed MESSENGER would traverse the distance from Earth to Earth’s Moon in only 1.7 hours!

Even at this great speed MESSENGER is slightly slower than the fastest spacecraft: Helios 2. That spacecraft – launched into a solar orbit on January 15, 1976 – reached a top speed of 157,078 miles per hour (70.220 kilometers per second) relative to the Sun in April of 1976.

Because of MESSENGER’s near-perfect Mercury flyby trajectory on October 6, the mission design and navigation team decided that a trajectory-correction maneuver (TCM) scheduled for October 28 will not be needed. The next maneuver for the mission, scheduled to be carried out in two parts on December 4 and December 8, will re-target the spacecraft for the third and final encounter with Mercury in just under a year on September 29, 2009.

New Color Images of Mercury Available

The MESSENGER Science Team has released five new images from the probe’s second flyby of Mercury. To the human eye, Mercury shows little color variation, especially in comparison with a colorful planet like Earth. But when images taken through many color filters – such as the 11 narrow-band color filters on the Mercury Dual Imaging System’s Wide Angle Camera (WAC) – are used in combination, differences in the properties of Mercury’s surface can create a strikingly colorful view of the innermost planet.

Here are four images of Mercury. The image in the top left is the previously released grayscale monochrome image taken with a single (430 nanometer) WAC filter; the remaining three images are three-color composites, produced by placing the same three WAC filter images with peak sensitivities at 480, 560, and 630 nanometers in the blue, green, and red channels, respectively. Shown here are two color images of Thākur, named for the Bengali poet, novelist, and Nobel laureate influential in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In both the optical navigation images and the full-planet WAC approach frame, a bright feature is clearly visible in the northern portion of the crescent-shaped Mercury. This Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) image resolves details of this bright feature, showing that it surrounds a small crater about 30 kilometers (19 miles) in diameter, seen nearly edge on.

This pair of images illustrates the dramatic effect that illumination and viewing geometry (i.e., the angle at which Sunlight strikes the surface, and the angle from which the spacecraft views the surface) has on the appearance of terrain on Mercury. And this NAC image, taken about 85 minutes after MESSENGER’s closest approach during the mission’s second Mercury flyby, shows a view of Astrolabe Rupes, named for the ship of the French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville. Rupes is the Latin word for cliff.

Additional information and features from this encounter will be available online at http://messenger.jhuapl.edu/mer_flyby2.html, so check back frequently to see the latest released images and science results!

MESSENGER (MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) is a NASA-sponsored scientific investigation of the planet Mercury and the first space mission designed to orbit the planet closest to the Sun. The MESSENGER spacecraft launched on August 3, 2004, and after flybys of Earth, Venus, and Mercury will start a yearlong study of its target planet in March 2011. Dr. Sean C. Solomon, of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, leads the mission as Principal Investigator. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory built and operates the MESSENGER spacecraft and manages this Discovery-class mission for NASA.